The Spencer Family Story Continued...

- Greg Austen

- Sep 15, 2025

- 15 min read

Updated: Sep 16, 2025

When starting down the path of family history research you never know just what you might find. The story of the Spencer family has proven to be fascinating. It has introduced me to a new part of England and its history, namely Leicestershire. It has also unveiled new family members with amazing stories.

Before starting this blog I must say a big thanks to my cousin Lorraine Spencer who I have just recently met and who has shared some wonderful information and photographs. Lorraine is another family member who undertook family history research in the days before we had the benefit of online research options. In our conversations Lorraine has given credit to Lucy Marshall who she knew as a driving force within the genealogy movement in New Zealand for many years. It is thanks to these people and those in our family who did the hard yards in the early days, that we can now so easily reach back into the past for information.

When we met, Lorraine handed to me a wonderful hand drawn family tree. This tree shows the Spencer family as far back as Robert Spencer who married Mary Berridge in December of 1627 in Countesthorpe. They had 15 children. Note the surname Berridge. Some 200 hundred years later Thomas Spencer married Elizabeth Berridge. Another interesting aspect of the tree is that the names Mary, William and Thomas appear in every generation of the Spencer tree, with the exception of the children of Thomas and Elizabeth. They did have a daughter named Mary but did not have a Thomas or a William.

The village of Knossington located to the north of Leicester is where we find the Whalebones house built by William Spencer in the early 1800s. However it is the village of Sapcote that was home to a number of generations of the Spencer family. It is where both William and his wife Mary were born. William's father Thomas was born in Sapcote and his grandfather John married Elizabeth Messenger from Sapcote, lived in the village and is buried there. He was born in Cosby.

During my research I came across the posting below.

Janet Finlay continues....

William Spencer (1772 - 1824)

William was the grandfather of Thomas Spencer who married Elizabeth Berridge and made the move to New Zealand.

William was born at Sapcote on 7 June 1772. His parents were Thomas Spencer born at Sapcote 31 August 1746 and Mary Harrison born at Sapcote 24 December 1744.

William married Mary Puffer on 20 April 1794. They had four children, William born 14 September 1795 , Mary born 28 February 1797, Thomas born 21 July 1799 (this Thomas was the father of Thomas Spencer born 17 April 1828 who married Elizabeth Berridge) and Arthur born 24 April 1803.

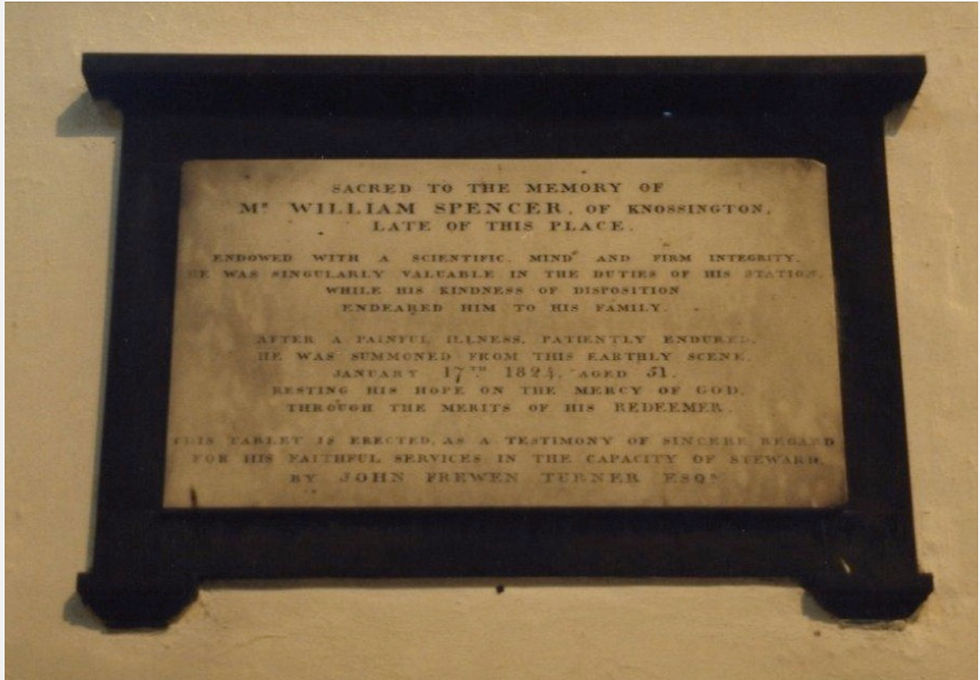

William was the owner and builder of the well known Whalebones house located in Knossington. He was very highly regarded by the residents of Sapcote and Knossington. So well regarded that he has a special tablet in his memory placed within the walls of the Parish Church of his home village of Sapcote.

The enscription on the tablet reads as below.

The tablet records that William served as Steward to John Frewen Turner Esq. John Frewen Turner was a major landowner and politician. He had inherited the manor of Cold Overton from his father the Reverend Thomas Frewen. John was also the High Sheriff of Leicestereshire. In his role as Steward William managed the day to day affairs of John Frewen's large estate.

During my research of William I came across a very interesting article written about William's role in the development of a Workhouse at Sapcote for the benefit of the local poor.

This document provides a very long and detailed description of William's efforts in building a Workhouse for the poor that would benefit the residents of Sapcote. I have selected some parts of the essay that I consider are great insights into William's work and into the general development of Workhouses to assist the poor.

Here is an extract from the introduction. It clarifies William's role.

On 1 February 1829, the major landowner John Frewen Turner died aged 73. The Leicestershire Chronicle reported that he was ‘greatly beloved and lamented’, a ‘true old English Gentleman, being the sincere christian , the faithful friend, the parent of his tenantry, and the benefactor of the distressed, and poor’.

But the poor were not always at the forefront of his mind. In 1806 Frewen Turner had to be encouraged by his land agent, William Spencer, to attend the opening of a new workhouse in Sapcote in Leicestershire. Like so many absentee landowners of the era, Frewen Turner’s land was left in the hands of a land agent who was partly responsible for the relief of the poor enshrined in the old poor laws – laws established and developed from the Elizabethan era, until the centralized New Poor Law was implemented from 1834.

This article provides a micro-history of the management of poor relief in one rural estate

in England by one land agent. Its purpose is to the demonstrate the ways in which land

agents could help landowners establish new poor relief regimes, especially institutional relief, in the final decades of the old poor laws, years when poverty was increasing dramatically. It does this by examining over 50 letters sent by William Spencer to Frewen Turner over an eight-year period, from 1804 to 1811, alongside surviving parish records. This correspondence provides numerous and rich details about Spencer’s involvement in the establishment of a new workhouse.

The section below provides information on Frewen's background.

Spencer’s employer, John Frewen Turner (born in 1755), inherited parts of Sussex, Leicestershire, and Yorkshire throughout the second half of the eighteenth century from various immediate and extended family. He came to own land in Sapcote in south-west Leicestershire and Cold Overton Hall, a seventeenth-century country house, in the Melton district on the eastern edge of the same county in 1791 on the death of his father, Reverend Thomas Frewen Turner. The Sapcote land was approximately 1600 acres and under Thomas Frewen Turner’s control it was enclosed in 1778. In the same year his son inherited the land, John Frewen (as he was then known) took up the additional surname Turner. He also became a magistrate, the deputy lieutenant-colonel of the yeomanry cavalry, and received the title of High Sheriff of Leicestershire. Within three years he became a Major of the Leicestershire Yeomanry, and in another three had secured the title of Lieutenant Colonel.These inheritances and powerful titles would ‘lay the foundations for the rise of one of Leicestershire’s major landowning families in the nineteenth century’.Frewen Turner became an MP for Athlone (1807–1812) in Ireland as an independent candidate, although it appears that he never spoke in the House. In 1808 he married Eleanor Clarke, the sister of the intellectual, feminist and Parisian salon host Mary Elizabeth Clarke (later Mohl) who visited Eleanor at Cold Overton Hall from time to time.

The section in bold lettering below gives excellent insights into William's background and his very important and wide ranging role.

It is unclear exactly when Frewen Turner first employed Spencer as a land agent, but it is

obvious that the employer valued and respected him. Spencer lived with his wife Mary in the

parish of Knossington, adjacent to the parish of Cold Overton. When he died in 1824, aged

51 years, Frewen Turner funded a memorial plaque, to which Mary’s name was later added.

This gesture is not surprising given that the agent had a ‘status closer to the nobility than the

tenant farmer’.The plaque, erected in Sapcote parish church, pointed towards all the standard qualities of the land agent. He was ‘endowed with a scientific mind and firm integrity he was singularly valuable in the duties of his station while his kindness of disposition endeared him to his family’. Like many other land agents of this era, he pushed the estate into new phases of ‘improvement’ beyond the agriculture of the estate, with plans for new bakehouses, turnpikes and clocks, amongst other things. He took notice of the infrastructure and services within the estate and surrounding areas, such as the time a hurricane in 1811 damaged all of the local windmills and completely demolished one in Hinckley. He also noted things in his capacities as schoolmaster, constable and churchwarden, such as sparse school attendance, robberies from grocery stores and from individual’s houses, and the impregnation of a ‘lunatic’ by a married man. He relayed bad news as well as good. Correspondence was Spencer’s way of securing the ‘confidence of his employer’, as Geoff Monks puts it, so that he could undertake his duties with self-assurance.

Spencer also oversaw poor relief matters for Frewen Turner in difficult circumstances. The

Midland counties were not immune to the economic depression that caused much destitution and hardship amongst the labouring classes. The £2 million spent on relief in England and Wales in 1783–85 had doubled by 1802–3 and then quadrupled to £8 million by 1818. Cost per head of the population went from 4s. in 1776 to 13s. in 1818. Leicestershire was providing 14s. per head of the population between 1812–13, 1s. higher than the average across England.

The section below provides an excellent summary of William's role and is very complimentary about his work.

In a letter in 1809, Spencer asked his employer to stop should he pass through the estate one day, so ‘that you may see the many improvements that have taken place since you was here last’. From Spencer’s perspective, such ‘improvements’ could have included the workhouse as well as other areas of estate management. Indeed, land agents such as Spencer were intensely involved in the provision of poor relief in the parishes they presided over on behalf of their employers.

Not only did they seek to improve the land and, as recent literature has demonstrated, tenure and facilitates within rural communities, they were also intimately involved in improvements, as they saw it, in the provision of statutory poor relief. The correspondence which flowed from Spencer’s study to Frewen Turner’s residences is rich and, in combination with surviving parish records, provides exhaustive details surrounding the establishment of a new workhouse. These letters give us a window into how deeply land agents could be involved in the administration of poor relief. Spencer had an important role in the founding of a new workhouse, the shaping of how it was managed, and sought out new policies and practices and ultimately reported on the progress of the regime and its impacts.

Spencer used his close attention to detail and research abilities to develop a good knowledge of how to implement Gilbert’s Act at Sapcote. The letters demonstrate that he secured the support of ratepayers in the locality, understood the intricacies of the Act, the importance of different workhouse committee roles, and who should ideally take them. He drew upon the knowledge of local men and fellow workhouse administrators residing in other parishes and unions, both near and far. Land agents were able to research and understand different modes of ‘best practice’ and identify new relief practices. He reported on the endeavours of the workhouse committee, such as when they considered adopting a workhouse uniform. This particular case revealed that the workhouse committee and Spencer understood what practices should not be adopted. To some extent, Spencer became a bank of knowledge on which his employer could draw, even leading him to be consulted on poor relief matters on estates he was not managing. Steven King compared the skills and attributes taught to potential new land managers on degree programmes today with those possessed by land agents of the past.

An interest in all matters financial was important, both then and today, including making

sound investments with minimal risks, but also and perhaps equally importantly careful

diplomacy was essential to nullify rumours and resolve disputes, as well as ‘stamina for lots

of travelling’ Such attributes were to be found in the land agents of the nineteenth century

implementing new welfare regimes.

I suspect there are many more aspects of William's life that would be interesting to explore. So far I have not found much more than is covered above and in my previous blog. The aspect of most interest to me at present is the matter of the Whalebones House and the farm lands connected to the Spencer family.

Looking at the various Census returns for William senior's three sons, the brothers William, Thomas and Arthur Spencer, it seems to me that they each may have shared in an inheritance consisting of land from their father's estate. I further think that Thomas either inherited or purchased the Whalebones house based on the connection that his son Thomas seems to have had to this property prior to his move to New Zealand.

I noted that the Census records for William Junior and his wife Anne indicate they lived at various addresses in Sapcote. These addresses appear to be within the village and not be part of any farm land. This is despite William being described on the Census records as a farmer of 200 acres of land. His brother Thomas is also described as a farmer with 200 acres of land and employing labourers on his farm. From checking the names of the farm workers at each address it does seem that these are separate farms and not one farm that was jointly owned.

The other brother Arthur appears to have lived at Knossington as a child but subsequently moved to Cold Overton. In the 1841 Census he is described as a grazier age 35. In 1851 Census he is described as a "Landed Proprietor" and is living at Oakham. Unlike his brothers William and Thomas no farm land or farm workers are listed for him in each of the above Census. Arthur died in 1860.

When considering the matter of the Whalebones House I went looking for a Will for Thomas Spencer and was fortunate in finding the document below.

Unfortunately this is a poor copy and is very hard to read in some important places. It is dated the 21st day of November 1854. Thomas died on 3 May 1856 (age 57) at Knossington.

The key aspects I have been able to establish from this are;

Thomas left his wife Catherine (Kate) all the household furniture and an income of 100 pounds per annum for the rest of her life. Kate died in 1870 age 65.

He left his son Thomas a silver coffee pot, his son Harrison a silver cup, his son Joshua a tea pot and silver cup, his son George his lathe and tools and son Albert all his books. His daughter Mary was left a silver cream jug and a sugar item of some sort that I cannot decipher.

Two houses in East St, Leicester occupied by some people whose names are unclear are given to Mrs (name unreadable, possibly surname York) a lady who is in the United States, on condition that she gives Thomas title to her "moiety" (share) of (something unreadable) at what could be Croft. The reference to Croft may mean that this provision has some connection with the involvement Thomas had in gravel quarrying. He is known to have had an involvement in quarry ownership in Sapcote and Croft was a place with a very large quarry.

All his other property whatsoever and wherever "I give to my surviving surviving children to be equally divided amongst them except my son Thomas who is to get six hundred pounds sterling less than the others to be paid with interest on arriving at the age of twenty one and I hereby appoint my wife and my sons Thomas and Harrison to be the Executors of my will signed sealed and delivered by the above Testator at his request in the presence of ....."

The provision for son Thomas to get 600 pounds less than the others is significant. I take it to mean he has already received something of a similar value and that this provision offsets that in order to equalise each son's inheritance. Perhaps this was the Whalebones house. In 1854 Thomas was already age 26. The reference to age 21 is therefore most probably in respect of the other sons who will receive their share of their fathers estate "with interest" when they each reach age 21.

William Spencer baptised 14 September 1795

In the section of this blog that follows I move to another William, namely the other son of William and Mary (and brother of Thomas whose Will is discussed above) who was born in 1795 at Sapcote. He married Anne Pougher on 4 January 1826 in Sapcote. They had 8 children. The story below is about their sons John and Thomas.

I was fortunate in finding a photograph that is of John and Thomas and their older brother William. John is standing on the left, William is seated in the middle and Thomas is on the right.

John and Thomas Spencer- Printers and Publishers of Leicester

The names John and Thomas Spencer kept appearing in various of my searches of information on the Spencer family from Leicester. They were usually shown in connection with a publication called Leicestershire & Rutland Notes and Queries. This document was described as a quarterly magazine. Of course a google search took me to copies of this publication and furthermore I was able to access digitised versions of two of the volumes. It is also possible to purchase examples of the original documents online- at a significant price.

My curiosity was aroused so I started digging further. It was not obvious to me how John and Thomas fitted into the Spencer family. However I was certain that a connection must have existed as the photo of a John Spencer that I have included above was with the photographs shared with me by Lorraine.

I was very fortunate in finding that a memorial to John Spencer had been published within one of the Notes & Queries books. I have copied this below.

With the information from John's memorial and some additional searching I was able to find where he and Thomas sat within the Spencer family tree.

The story that has unfolded is another insight into the manner in which this family's interest in printing and photography evolved into successful business enterprises. Below is a copy of an advertisement that appeared in the Leicester Journal in April of 1866. If you read down the left side column you will see that John and Thomas had a very well diversified business. It consisted of the following;

Spencer's Library- said to have 500 subscribers

Bookselling- English and Foreign books

Printing- by Steampower!

Book Binding- from the plainest to the most elegant

Stationery- account books of all descriptions, envelopes, artists materials etc

A Picture Gallery- works of art at greatly reduced prices

Photography- every improvement and novelty in the Photographic Art

When reading the above descriptions of the Leicester business I could not help but see where the printing business established by Edmund and Albert Spencer probably gained its inspiration. My assumption is that their father Thomas suggested that Edmund and Albert follow the example set by their cousins John and Thomas in Leicester. The Leicester business was in operation from the 1860s through to the early 1900s. We know that Edmund made a visit to England in the 1880s. Perhaps he visited his cousins and viewed their business at that time?

In the case of Albert we know that he started out in business by learning the art of photography and initially set up a photography studio in 1887. Two years later he moved into engraving and printing. Many of the items listed in the advertisement above as printing and stationery supplies offered by John and Thomas were offered as products by Albert and Edmund.

As we now know Albert took that model in an entirely new direction when he added rolls of toilet paper to his range of paper products! I would love to know how he arrived at the point of realising there was a lot of money to be made from toilet paper and similar paper tissue products. Was there a sudden moment of inspiration one day?

Sadly John and Thomas did not fair well with the longer term success of their business. The newspaper article below reveals that their business went into receivership in 1891. They had been operating since 1853. This suggests that over a long period of time they did have a successful business. However it ultimately struck some financial problems that could not be overcome. It is also apparent that John was unwell for several years prior to his demise in May of 1892. His brother Thomas sadly died just over a year later in November of 1893.

The comments in the section of the newspaper report below reveal the properties used to secure loans to the business included some agricultural land. I have not seen any details of where the agricultural land that is mentioned was situated. It might have been a portion of the family land owned by their father. Given that their brother William took over managing that farm it seems likely the other sons would also have received an inheritance from their father of similar value. There is mention in the comments that follow of rents being received by John and Thomas on the properties they had borrowed against.

We know from the Census returns that John and Thomas's father William was in possession of a farm of 200 acres inherited from his father. Their brother William seems to have taken over running this farm at some stage following the death of their father in 1839 age only 54. At that time William was only age 12.

The 1851 Census below shows that at that date Ann was a widow and her son William at age 23 is the farmer of 200 acres. They also have a house maid, dairy maid and several farm workers. Note that the address is High St in the village of Sapcote.

In 1861 William is shown as head of the household at age 38 and his wife Selina as well as his mother Ann are at the same address. The census indicates that in 1861 William farmed 200 acres and employed 5 men and two boys. The house address is now Mill St in Sapcote.

His brother John age 32 is also listed and shown as a printer who employs 4 men and 5 boys.

In the 1881 Census William and his wife Selina are listed along with the dairy maid, house maid and two farm workers.

William died in 1894. He was the last surviving child of William and Anne. Their other children had all died at very young ages. Mary was only age 1, Arthur less than 1, Charles less than 1, Arthur 11 and Mary Ann 6.

Below is a newspaper report of the death of William. It indicates he left a widow and two daughters. It also indicates he had retired from his farm business and moved to Stoney Stanton. It also says he took a prominent part in agricultural matter and also like literature and music.

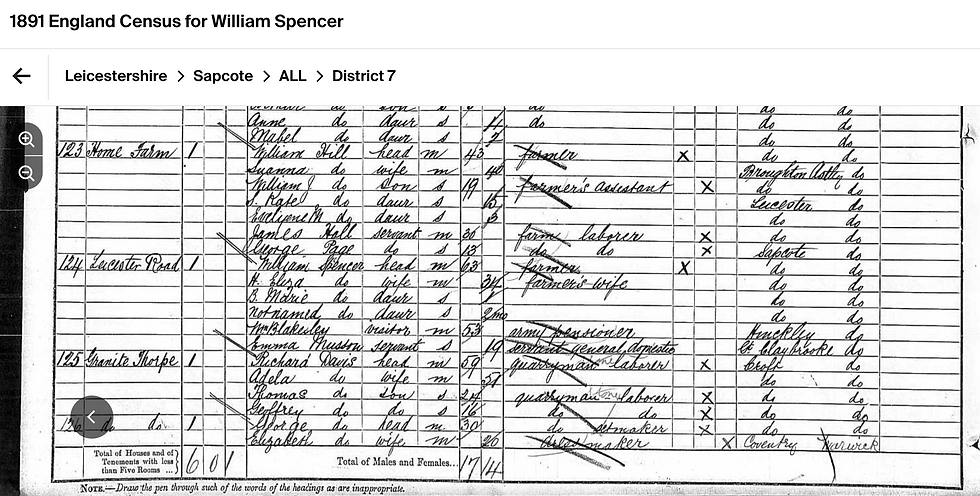

We know that Selina Spencer died in 1883. William remarried to Harriet Eliza Hill. They had two daughters Beatrice Marie born 1890 and Ethel Selina born 1891. This is reflected in the 1891 Census information shown below.

I remain uncertain at this point on the matter of the farmland connected to the three Spencer brothers William, Thomas and Arthur that was inherited from their father William. I think they each inherited farmland situated somewhere near either Sapcote or Knossington following William's death in 1824. Given their father's standing in the community, as evidenced in the article about the Workhouse, I believe it is reasonable to assume he had accumulated significant wealth and had a large estate. The size of the Whalebones House reflects this.

There are many more names in the family tree for me to explore. You can expect more blogs about this family to follow.

Comments